Majka Burhardt on Omega, Cannon Cliff, NH. Photo by Peter Doucette

In conjunction with Climbing Magazine and climbing.com. Read online HERE.

This is a story without a conclusion. Maybe that will change by the end. At this point, I’m not betting on it. Four weeks ago, I wrote a piece about trying to understand death in the face of more death, and in spite of life. I thought that, by writing it, I would move on from it—be released from it. But here’s the thing about writing about death: it creates conversation about death. And when you write about death and climbing, it creates a roar.

I can’t fully understand it, but I also don’t know if I am that surprised. I wrote about being scared as a climber. I wrote about questioning my choices. And suddenly, everyone else seemed to question my choices as well. My best friend from first grade wrote to ask me to please stick around until we are both old and can swap stories of our different lives.

“Maybe it’s time to reconsider the danger level,” he said. “I hope you are open to interesting twists and turns that may keep you in safer territory.”

I wrote him back: “I will be careful. I am careful. I am paying attention.”

My New York writing friend, a new mother, wrote and said, “Maybe it’s a good time to take it easy. I’m serious.”

I sent her a similar response to what I sent my grade-school friend, and as I typed it, I believed it, but I also wanted to take it back. I didn’t really want to send a response at all. I didn’t really want the note from her in the first place. I didn’t want to be reproached. And even though I knew it was out of love, I didn’t want to be questioned. It might have been because I didn’t want the questions to get in my way. But really, it was because all the answers I could come up with sounded hollow and weak. But I still typed them onto the white space on my computer. What else was I supposed to do?

My grandmother has known I “climb” for over a decade. I don’t think she’d ever really understood what climbing meant, however, until a close family friend was killed on Denali. Now, she wants details. This past weekend we talked on the phone:

“What did you do today?” she asked me.

“Oh,” I said, “I spent some time outside and then…”

“Climbing? Did you go climbing?”

I was in my van with my hands still caked in chalk. She was in her bed with an ice pack over her cataracts. “Well, Gram. You see. It’s different…”

“You did,” she sighed. “I wish you wouldn’t.”

“I was rock climbing though, it’s safer and, well, it was close to home and…” I didn’t want to make the comparisons, but didn’t know what other choice I had. “It’s not mountaineering, Gram. Or ice climbing, or…”

My grandmother has had two quadruple bypasses and lives within a 300-foot radius of her nursing home bed. But she also has a master’s degree and all of her mental facilities.

“But Majka,” she said. “You ice climb.”

I was quiet.

“In the winter, you ice climb.”

We’d all like for what we do to be different. I want to explain to the non-climbers in my life why what I am doing is different than what the friends I have lost were doing when they died. I think this will help, or should help. This is likely a similar response to the old adage of climbing being no more dangerous than driving. Right now, however, it’s a load of crap. There have been too many people who have gone in too many ways. There is only so far one can split a hair. It is all climbing.

I had dinner this past month with a woman in her 40’s who has just started climbing.

“I love it,” she said. “I can’t get enough of it.”

She was scarfing down a burger and a beer. Her face had the telltale glow of her first wind-scouring alpine route. I wanted to cloak myself in her excitement just as much as I wanted to rip it to pieces with inappropriate stories of death that she did not really need to hear.

When people tell me to be safe, I immediately want to ignore them. I want to tell them, in an exasperated voice, of course, leave me alone, do you think I’m not already planning on that? Maybe that resistance is bred into us early on as climbers. Maybe we have to be that hardheaded to do it in the first place. And then, that separation from danger keeps us doing what we love.

I’m not saying that from a factual standpoint, that we don’t know that what we are doing has inherent risk. But if we spend all of our time thinking about that risk, we wont climb. I know, I’ve tried. Everyone around me, it seems, is trying.

A friend told me over dinner that she is having panic attacks. “On 5.7’s.”

She can climb 5.12.

“Maybe,” I said to her, “you’re finally having the normal human response. It just took this to have it.”

Would this be any different if we lived different lives? Is it insensitive or incorrect to think about people in Darfur, people in the military, people who die from starvation? Is there any way not to? Is death any easier if you are surrounded by it daily, if you finish one funeral meal and prepare for another? These recent looses seem seminal in my life, and even more so in the lives of others. I am not suggesting they should have less impact. I’m just wondering what to make of the weight of this, in the context of the privilege it seems we have as compared to others for whom death comes much more often. Maybe these two thoughts don’t go together. But they keep doing just that in my head. What do we owe to that privilege? How can we fully absorb the responsibility?

When I was twenty, my fiancé’s best friend was killed in an avalanche. I was new to climbing, and ever since then, climbing was always complicated by loss—or, at least, the threat of loss. And then, horrified, I saw it play out in all of those ways for others. I have lived on both sides of this since that moment thirteen years ago. I have been the climber, the climber’s girlfriend, the one who has the epic, the wife at home when the epic is going down who envisions becoming a widow, the ice climber who steps out of the way of the falling rock just in time, the climber coming home a day late with no phone call to the non-climbing partner, and now, again, the woman who alternates between her own climbing excursions, and being the one at home looking out the darkening window and waiting for her partner to come back from the mountains or the crag.

But no matter what the role, loss was something I feared being foisted upon me—not what I feared foisting upon others. I’d never really realized that until now—when I have seen the ricocheting effects of loss on brothers, aunts, friends, ex-partners, enemies, co-workers—when I have felt the collective weight of loss in a community. I see this, and I have to call myself out on my own myth that my fear is limited to loosing my partner. Equal to that fear is now the fear of the impact of my death on those who love me. And so I can’t help but have two sets of responses to this new heightened sense of danger. Part of me does not want the restriction that comes along with it. The other part of me wants to impose the same restriction on the ones I love.

Is this too dark? Is it too light? I told you I would not get to a conclusion. I haven’t wanted to write more about this, but each time I open my email I see another note, each week I get another phone call, each time I re-connect with a friend, it takes less than ten minutes for us to be talking about death. This was not the case five months ago.

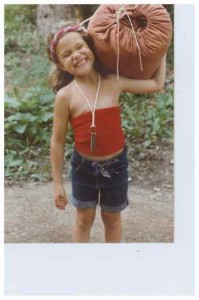

Me, back when it all started

If you are tired of all of this, I will say this: I am, too. But I am not exasperated. I am tired in the way that all adults rub their eyes like children when they need to go to sleep. Maybe we are supposed to grow tired so that we revert back to that state of infancy in our climbing. When those first normal moments of fear and apprehension were equal to the elation and excitement. Maybe we should spend more than a moment here. Maybe I should.

It has been a long time since I have been here. Back when I started climbing, all I wanted was to get rid of that moment of hesitation and grab the achievement and the ecstasy. Perhaps growing older, in the midst of loss, and in recognition of the privilege of life, deserves a re-visitation to that very first point where fear was natural and the full meaning of danger was acknowledged—even if just for a moment. And if I truly do that, then I can’t tell my friends or my grandmother that what I do is not dangerous anymore.

I don’t really have a plan for what I will tell them instead. But for now, it seems like the right idea to listen to them with respect. And then, when I find myself looking up at a incipient seam of granite or ice, to take that same respect with me on my way.

Read Part One of this Story at: Screaming Uncle at a Whisper