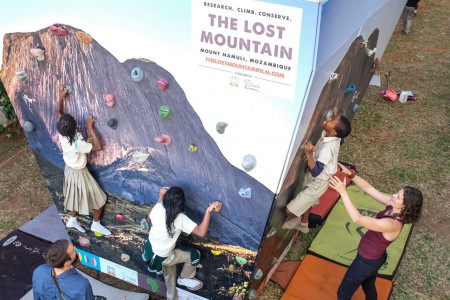

Exactly one month ago I tightened the last bolt in the last hold on the first-ever climbing boulder in Mozambique—and then climbed on it with over 1,000 Mozambican school children.

Exactly one month ago I tightened the last bolt in the last hold on the first-ever climbing boulder in Mozambique—and then climbed on it with over 1,000 Mozambican school children.

Tonight, over dinner in Central Mozambique, I made a promise to climb a 12-pitch run-out granite slab with a Mozambican farmer named Elias who’s never roped up in his life.

Tomorrow, I meet 25 African students in Gorongosa National Park to spend 10 days exploring the vortex of conservation, science, leadership, stewardship and adventure.

And all of this started because of a blurry photo of a mangy rock face.

This is not the way this story was supposed to go. When my friend Marc Chauvin flipped me the blurry rock face image four years ago, it looked interesting. Interesting in the way my nephews charcoal art drawings of the family poodles are interesting. He shot the picture out of a moving train in northern Mozambique. The face had all of the typical features of something worth climbing—it looked steep, it was granite, and it was sizeable. But it was also covered by irregular deep brown and black stripes. Fuzzy stripes. Stripes that were probably thick vegetation.

18 years ago, when I committed to climbing full-time, I envisioned a life of perfect splitters on impeccable rock on endless towers around the world. I poured over images of destinations. But then I started looking—and seeing—behind the photos.

Behind this photo, it turns out, is a region with some of the greatest biodiversity in Mozambique/Africa/the World. When I discovered this I decided two things: I was going to climb in Mozambique, and I was going to take scientists with me.

A few months, hundreds of emails and uncountable late nights of internet roaming later I knew something else: I was going to take these scientists climbing on Mount Namuli—a mountain with over 4,500 people living on its flanks. Which meant that this wasn’t an expedition that would happen in a vacuum. This expedition, and all it sought to achieve, needed to happen with the community. And so the Lost Mountain was born.

The Lost Mountain Initiative is an international venture to foster a future where people and ecosystems thrive together on Mount Namuli. It took off, after years of planning, in 2014 with an expedition combining rock-climbing, cliffside scientific research, integrated conservation planning, and media. We’re now working to create targeted, measurable conservation and human livelihood gains on Mount Namuli and scale this approach to other mountain regions and communities.

I’ve known since the beginning that the Lost Mountain was never going to be a one-off expedition. The roots have always been about going bigger, doing more, and involving as many passionate actors as you can pack into a truck, a bus, a plane, or a country twice the size of France.

Mount Namuli is 1200 miles from Maputo and 7,936’— so it’s a tad bit hard to move. Which is why it made all the sense in the world to build a 14-foot high boulder wallpapered with a photo of Mount Namuli to the middle of Maputo last month and share it with hundreds of kids and the President of Mozambique.

Last month I was in Maputo, Mozambique for the launch of Biofund Mozambique—a 20 Million USD fund for conservation in a country that the United Nations Development Program ranks as the third poorest country in the world and where the majority of news coverage points to the country’s emergence from a tumultuous civil war in 1992. Mozambique also has 14 major ecological regions, massive mountains, numerous endemic species… and amazing granite. Especially if you’re willing to run it out.

When Kate Rutherford and I established our new route on Mount Namuli in 2014 we slung grass clumps and climbed with a mix of levitation/all points on mentality I usually reserve for ice climbing. Thankfully I didn’t have to encourage the same with the kids on the boulder in Maputo. Instead I stuffed fake snakes and ants in the climbing holds and told them to “climb for the cobra.”

Sometimes I just go climbing. Lots of time, actually. But not on Namuli or with Namuli. Namuli is so much more than a granite mountain. It is home for thousands of people, it is the watershed for them and thousands more, it is a critical link in the region’s biodiversity. Which is why my team and I built the boulder to share Namuli’s story.

To build the boulder, to rope up with Elias the farmer, and to host some of this continent’s best and brightest students in a challenging, academic forum on conservation and adventure is more than I could have imagined when I saw that blurry photo.

As I am learning, Mount Namuli holds the wisdom of this region’s past and the keys to a vibrant future. You don’t lead an expedition to Mount Namuli, Namuli sends you on a journey.

So when people ask me, “You’re the climbing project?” Or, “you’re with the mountain?”

I only have one answer, “Damn straight I am.”

MORE:

Simple:

Learn more: www.thelostmountain.org

Follow the Lost Mountain Symposium—happening through July 22nd in Mozambique.

DETAILED:

The Lost Mountain Initiative is an international venture to foster a future where people and ecosystems thrive together on Mount Namuli, Mozambique. The Initiative began with a 2014 field expedition combining rock-climbing, cliffside scientific research, integrated conservation planning, and media. www.thelostmountain.org

The Lost Mountain Initiative is currently working to create targeted, measurable conservation and human livelihood gains on Mount Namuli and scale this approach to other mountain regions and communities.

In July 2015, the Lost Mountain Team is also hosting the Next Gen Symposium – a 12-day symposium to launch conversation on “disruptive” conservation–a new model for building community-driven conservation in some of the world’s most remote and biologically diverse places in the world. 25 African students have full-ride scholarships to attend the Symposium to explore conservation planning and management principles, leadership development models, Leave No Trace techniques, and examinations of contemporary challenges facing conservation and development

Mount Namuli is a 7,936-foot granite monolith and the largest of a group of isolated peaks that tower over the ancient valleys of northern Mozambique. It is one of the world’s least explored and most threatened habitats. Here, plants and animals have evolved as if on dispersed oceanic islands, so that individual mountains have become refuge to their own unique species of life, many of which have yet to be discovered or described by science. Biologists and conservationists from around the world have identified Mount Namuli as a global hotspot: a place of critical biodiversity and an opportunity to model a new vision for wildlife preservation that integrates the wishes and needs of local people.